Hermite Polynomials and Applications in ML

The Key Points

The power of Neural Networks is largely derived from the ability to generate complex, non-linear functions for data processing. This marks a significant departure from classical model-based approaches, which often rely on linearity assumptions. Traditional tools such as the Fourier Transform, spectral methods, eigenfunctions, and least mean-square error (LMS) estimators lose their theoretical justification when linearity is removed. Interestingly, the challenge of designing non-linear processing is not new. Foundational work in this area includes Wiener’s works on the Volterra Series and multivariate orthogonal polynomials, which is now a largely overlooked literature known as the Wiener G-Functional Expansion, or the Wiener-Hermite Expansion. This page aims to provide a tutorial on these concepts in the context of modern machine learning applications. In particular, we will explore the connections between these classical techniques and the emerging field of Reservoir Computing, also with our own research on H-Score Networks.

There is a huge literature related to orthogonal polynomials, or more specifically to the Hermite polynomials. Some of the treatments can be quite elaborate, involving complex analysis and combinatorics. Some references are hard to find these days. We will also try to include some of the older papers or present the shortest proofs we know to some of the important classical facts.

What are Hermite Polynomials: Definitions and Notations

There are several versions of the Hermite Polynomials defined in the literature. Unfortunately, we won’t use any of them, but will define our own before making connections to the more widely used notations.

To start, we denote \({\mathcal N}(x; \mu, \sigma^2)\) as the Gaussian probability density function (pdf) with mean $\mu$ and variance $\sigma^2$ for variable $x$. We often call this distribution a reference distribution.

- Definition: Hermite Basis Functions

- For a given reference distribution as a Gaussian density function \({\mathcal N}(x; \mu, \sigma^2)\), the Hermite polynomials are the sequence of polynomials $\phi_0, \phi_1, \ldots, \phi_k, \ldots$, where $\phi_k(\cdot; \mu, \sigma^2): \mathbb {R \longrightarrow R}$ is a $k$-degree polynomial, with parameter $\mu, \sigma^2$, and satisfy

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:Hermite} \langle \phi_i(\cdot;\mu, \sigma^2), \phi_j(\cdot; \mu, \sigma^2) \rangle \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \; {\mathcal N} (x; \mu, \sigma^2) \cdot \phi_i(x; \mu, \sigma^2) \cdot \phi_j (x; \mu, \sigma^2) \; dx = \delta_{ij} \end{equation}

Remark: The Reference Distribution and Change of Parameter

The Hermite basis functions are defined with the parameter $\mu, \sigma^2$, i.e. the Normal distribution used to define the inner product. We can define the “standard” Hermite basis functions as $\phi_k(\cdot; 0, 1)$, i.e. defined with respect to the standard Normal distribution. When $\mu=0$, we often drop that parameter and write $\phi_k(x; \sigma^2)$; and when $\mu=0, \sigma^2=1$, we may drop both the parameters and write $\phi_k(x)$ for convenience.

There is a simple conversion between basis functions with different parameters as follows.

- Proposition: Change of Parameter

- For any $k, \mu, \sigma^2$ and any $x$,

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:change_parameter} \phi_k(x; \mu, \sigma^2) = \phi_k\left( \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}; 0, 1\right) \end{equation}

This can be verified with a simple change of variable.

We only need to verify that with $s = \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}$:

\[\begin{align*} & \int_{-\infty}^\infty {\mathcal N}(x; \mu, \sigma^2) \cdot \phi_i \left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}; 0, 1\right) \cdot \phi_j \left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}; 0, 1\right)\; dx\\\\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty {\mathcal N}(s; 0, 1) \cdot \phi_i(s; 0,1) \cdot \phi_j(s; 0, 1) \; ds \\\\ &= \delta_{ij} \end{align*}\]Remark: These basis functions are closely related to Hermite Polynomials.

We deliberately use a slightly different notation and a different name to separate the basis functions from the existing terminology on Hermite polynomials. There are many nice properties the Hermite polynomials, but we will use only a few of them. For example, our discussion is generally known in the literature as the “Hermite Expansion”, which starts with a key fact that the basis functions in our definition form a complete basis to all L2 functions

Relation to the literature and Some Known Properties.

In the literature, the “probabilist’s Hermite polynomials” are defined as

\[He_n (x) = (-1)^n e^{\frac{x^2}{2}} \frac{d^n}{dx^n} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}\]which satisfy the orthogonality condition

\[\int_{-\infty}^\infty He_i(x)\cdot He_j(x) \cdot e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \; dx = \sqrt{2\pi}\cdot i! \cdot \delta_{ij}\]These are nice because the resulting polynomials are monic, and because there is a nice recursion as

\[He_{k+1} (x) = x \cdot He_k(x) - He_k'(x)\]In our development, we do not care much about how to find the Hermite polynomials, or how complex are the coefficients. We thus choose a more convenient normalization

\[\phi_k(x) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{1}{\sqrt{k!}} \cdot He_k(x)\]so that the basis function have unit energy.

For the sake of completeness, I will also hide a few important facts about Hermite polynomials in here.

- Proposition: Hermite Expansion

- For an $L_2$ function $f(x)$, we have

where

\[d_k = \frac{1}{\sqrt{k!}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{d^k f(x)}{dx^k} \cdot {\mathcal N}(x; 0,1)\; dx\]Proof:

By the definition of $\phi_k}’s as a complete orthogonal basis, we have

\[d_k = \int {\mathcal N}(x; 0, 1) \cdot f(x) \cdot \phi_k(x) \; dx\]This is where we need the definition of the Hermite polynomials:

\[\begin{align*} d_k &= \int \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \cdot f(x) \cdot \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{k!}} \cdot (-1)^k e^{\frac{x^2}{2}} \frac{d^k}{dx^k} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \right) \; dx\\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{k!}} \cdot \int (-1)^k f(x) \cdot \frac{d^k}{dx^k} \mathcal N(x; 0,1)\; dx \end{align*}\]Now the integral needs a $k$-step integral by part to get the desired coefficient.

- Proposition: Generating Function

Proof:

This is a simple application of the Hermite expansion result above. Consider $f(x) = e^{xt}$ as a function of $x$:

\[\begin{align*} f(x) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{d_k}{\sqrt{k!}} \cdot He_k(x) \end{align*}\]where

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d_k}{\sqrt{k!}} &=\frac{1}{k!} \int_{-infty}^\infty {\mathcal N}(x; 0, 1) \cdot \frac{\partial^k}{\partial x^k} e^{xt} \; dx\\ &= \frac{1}{k!} \int_{-infty}^\infty {\mathcal N}(x; 0, 1) \cdot t^n \cdot e^{xt} \; dx\\ &= \frac{1}{k!} t^n \cdot e^{\frac{t^2}{2}} \end{align*}\]which finishes the proof.

- Propositiion:Recurrence Relations

Proof:

The first identity is also known as Hermite polynomials are an “Appell sequence”. To prove it, we start with the generating function property

\[e^{xt - \frac{t^2}{2}} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{t^k}{k!} \cdot He_k(x)\]Take derivative w.r.t. $x$ on both sides,

\[\begin{align*} \mbox{On the LHS:} \quad \frac{\partial}{\partial x} (e^{xt - \frac{t^2}{2}}) &= t \cdot e^{xt - \frac{t^2}{2}}\\ &= t \cdot \left(\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{t^k}{k!} \cdot He_k(x)\right)\\ \mbox{On the RHS:} \quad \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{t^k}{k!} \cdot He_k(x)\right) &= \sum_{k=0}^n \frac{t^k}{k!} \cdot He'_k(x) \end{align*}\]The coefficients on $t^{k}$ must be equal, which gives

\[\frac{He'_k(x)}{k!} = He_{k-1}(x){(k-1)!}\]The second identity is a direct consequence of the definition:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{d}{dx} [{\mathcal N}(x; 0,1) \cdot He_k(x))] &= \frac{d}{dx} \left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \cdot (-1)^k e^{\frac{x^2}{2}} \frac{d^k}{dx^k} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}\right]\\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} (-1)^k \frac{d^{k+1}}{dx^{k+1}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \\ &= (-1) {\mathcal N}(x; 0,1) \cdot He_{k+1}(x) \end{align*}\]The last one follows by plugging in the definition of the normalized basis functions.

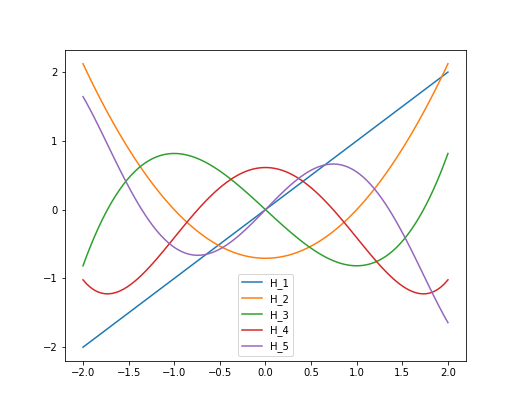

Finally, here are the first a few standard Hermite polynomials and a plot.

Informative Features from Observation with Gaussian Additive Noise

The first fact of Hermite polynomials that we will use is the Mehler’s Formula. This was proved in some classical results

- Theorem: Mehler’s Formula

-

Consider $X, Y$ as bi-variate Normal random variables with zero-mean, and covariance matrix

We define the likelihood ratio function as

\[L_{XY}(x,y) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{p_{XY}(x,y)}{ p_X(x) p_Y(y)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \exp \left(-\frac{\rho^2 x^2 + \rho^2 y^2 -2\rho xy}{2(1-\rho^2)}\right)\]then

\begin{align} \label{eqn:Mehler} L_{XY}(x,y) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty {\rho^k} \phi_k(x) \cdot \phi_k(y) \end{align}

The first thing to recognize from this fact is that with the orthogonality between $\phi_k$’s, what is written out is a singular value decomposition of the density ratio on the left hand side. If we further recognize that the $k=0$ term is $1$, Mehler’s formula can also be written as

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:svd} \frac{p_{XY}(x,y)}{ p_X(x) p_Y(y)} -1 = \sum_{k=1}^\infty {\rho^k} \phi_k(x) \cdot \phi_k(y) \end{equation}

This is very similar to the concept of Modal Decomposition in the series of our posts on the H-score. The slight difference is we studied the modal decomposition of the point-wise mutual information (PMI) function, which is the log density ratio; and here, we define the decomposition of the density ratio $L_{XY}$ minus $1$. The two are equivalent if we allow a “local approximation.”

Mehler’s formula is known to be not trivial to prove. A 1933 paper

Our proof to the Mehler’s formula.

The key step is to consider instead of jointly distributed $X,Y$ as in the Theorem, we define $Z = X + W$, with $W$ being an additive noise with $W \sim \mathcal N(0, \sigma_W^2)$, and $Z = \sqrt{1+ \sigma_W^2} \cdot Y$ as a scaling of $Y$. To make this consistent with the original setting, we need

\[\rho = \frac{1}{1+\sigma_W^2}.\]With this scaling, the Mehler’s formula becomes

\[L_{XZ}(x,z) = \frac{p_{XZ}(x,z)}{p_X(x)p_Z(z)} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \rho^k \phi_k(x) \cdot \phi_k(z; 1+\sigma_W^2)\]Recognizing this is an SVD structure, all we need to prove is for all $z$

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:scaled_Mehler} \int p_X(x) \cdot L_{XZ}(x,z) \cdot \phi_k(x) \; dx = \rho^k \phi_k(z; 1+\sigma_W^2) \end{equation}

This should be read as an inner product between $L_{XZ}(\cdot, z)$ and $\phi_k(\cdot)$, weighted by $p_X = {\mathcal N}(\cdot; 0, 1)$. We can rewrite this integral as

\[\begin{align*} \int p_{Z\vert X}(z\vert x) \cdot (p_X(x) \cdot \phi_k(x)) \; dx = \rho^k \cdot (p_Z(z) \cdot \phi_k(z; 1+ \sigma_W^2)) \end{align*}\]This new form works if we replace $Z$ by $Y$ and do the proper scaling of the basis functions. It is now clear why this particular scaling is the easiest: the conditional density $p_{Z\vert X}(z\vert x) = {\mathcal N}(z-x; 0, \sigma_W^2)$, which makes the integral a convolution.

\[\begin{equation} \label{eqn:induction_target} \int {\mathcal N} (z-x; \sigma_W^2) \cdot ({\mathcal N}(x; 1) \cdot \phi_k(x)) \; dx = \rho^k \cdot ({\mathcal N}(z; 1+\sigma_W^2) \cdot \phi_k(z; 1+ \sigma_W^2)) \end{equation}\]We will see how this makes the proof really easy.

First, since $\phi_0(x; \sigma^2) =1$, the above is clearly true for $k=0$.

Now, by induction, suppose \eqref{eqn:induction_target} is true for case $k$. We take derivative $\partial/\partial z$ on both side.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial}{\partial z} (\mathsf {LHS}) &= {\mathcal N}(\cdot; \sigma_W^2) * \frac{\partial}{\partial x} ({\mathcal N}(x; 1) \phi_k(x)) \\ &= {\mathcal N}(\cdot; \sigma_W^2) * (- \frac{\sqrt{k+1}}{\sigma}{\mathcal N}(x; 1) \phi_{k+1}(x))\\ \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial z} (\mathsf {RHS}) &= \rho^k \cdot \left( - \frac{\sqrt{k+1}}{\sqrt{1+\sigma_W^2}} ({\mathcal N}(z; 1+\sigma_W^2) \cdot \phi_{k+1}(z; 1+ \sigma_W^2) \right) \end{align*}\]The desired result follows directly from this. In both steps above we used the recurrence relation of the Hermite polynomials.

\[\frac{d}{dx} [{\mathcal N}(x; 0,\sigma^2) \cdot \phi_k(x; 0, \sigma^2)] = -\frac{\sqrt{k+1}}{\sigma} [{\mathcal N}(x; 0,\sigma^2) \cdot \phi_{k+1}(x; 0, \sigma^2)]\]The proof of this is included in the collapsed session titled “relation to the literature”.

Mehler’s formula with the fact that $\phi_k(x)$’s are a complete orthonormal basis leads to the following useful fact.

- Proposition: Modal Decomposition

- For the bi-variate Normal distributed $X,Y$ defined in the Mehler’s Formula, suppose

Then we have

\[\mathbb E[f(X) |Y=y ] = \sum_k \alpha_k\cdot \rho^k \cdot \phi_k(y)\]Proof:

This can be verified as follows:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbb E [f(X)|Y=y] &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{p_{XY}(x,y)}{p_Y(y)} \cdot f(x) \; dx\\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty p_X(x) \cdot L(x; y) \cdot f(x) \; dx\\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty p_X(x) \cdot \left(\sum_l \rho^l \cdot \phi_l(x) \phi_l(y) \right) \cdot \left(\sum_k \alpha_k \cdot \phi_k(x)\right) \; dx \end{align*}\]Use the orthogonality between $\phi_k$’s, we get the desired fact.

This fact can be used to generate the following important properties:

- $\mathbb E[\phi_k(X) \phi_l(Y)] = \rho^k \cdot \delta_{kl}$. That is, the Hermite basis functions evaluated on $X$ and $Y$ have an one-to-one correspondence, with descending correlation coefficient.

- The Hermite basis functions are the solutions for the HGR maximal correlation problems

. That is

- The optimization above can be solved with the Alternating Conditional Expectations (ACE) algorithm.

In our previous post, we defined Modal Decomposition, which breaks down a given statistical dependence between $X$ ad $Y$ into a sequence of pairwise correlation between pairs of features $f_i(X)$ and $g_i(Y)$ for $i=1, 2, \ldots$. The Hermite basis functions are the solution to this decomposition to the special case with bi-variate Normal distributed $X, Y$.

Related to this, we also developed in the follow up posts that in general, the correlated pairs of feature functions can be learned from samples using the H-Score Network. Specialized to the bi-variate Normal case, we in fact do not have to learn these feature functions as we already have analytical solutions to them. Alternatively, if we see people learning representations of data by adding Gaussian noise to it, (yes! we mean diffusion models,) we should know what feature functions they try to learn.

Multi-Variate Hermite Polynomials

Polynomials are a natural way to study non-linear functions extending from our understanding of linear functions. Most of the power of neural networks comes from generating non-linear functions of high-dimensional input. A classical tool to study multivariate non-linear functions is the Wiener Series, which is closely related to the Volterra Series and the so-called Wiener-Hermite expansion. This approach was first used by Wiener to analyze non-linear systems with memory. The input to the non-linear function is a collection of past samples—information the system “remembers”—which is then mapped to an observable output. Wiener’s aim was to parameterize all such multivariate non-linear functions by expressing them as linear combinations of multivariate polynomials.

A multivariate polynomial over $M$ variables with degree $K$ is a function $f : {\mathbb R}^k \to \mathbb R$, which can be written as

\[\begin{align*} f(x_1, \ldots, x_M) &= \sum_{k=0}^K H_k(x_1, \ldots, x_M) \\ &= H_0 + \sum_{k=1}^K \sum_{i_1 = 1}^m \cdots \sum_{i_k = 1}^m h_p(i_1, \ldots, i_k) \prod_{j=1}^k x_{i_j} \end{align*}\]where $H_k$ is a degree-$k$ polynomial, written as a linear combination of terms, each as a produce to $k$ variables (allow repetition) chosen from the input variable set.

One can see the indexing quickly becomes cumbersome: it can be done, but makes the real concept hidden behind heavy notations. A general polynomial of $M$ variables up to degree $K$ can have ${M+K} \choose K$ monomial terms. In other words, the space of all polynomials with $M$ variables and up to degree $K$ has ${M+K} \choose K$ dimensions. For example, for the case $M=2, K=3$, a polynomial can have a constant term, and terms on $x_1, x_2, x_1^2, x_1x_2, x_2^2, x_1^3, x_1^2 x_2, x_1x_2^2, x_2^3$.

The dimension counting for polynomials is a standard problem in combinatorics.

The problem of forming a monomial with up to $M$ variables and $K$ degrees is a “stars and bars” problem. Consider we have $K$ stars and $M$ bars, and we would like to arrange them in a line of $M+K$ positions. We can count the number of stars before the first bar as the power of $x_1$; the number of stars between the first and the second bar as the power of $x_2$; etc. For example, if $M=3, K=5$,

- ”\(*\vert **\vert **\vert\)” corresponds to $x_1 x_2^2 x_3^2$;

- ”\(\vert \vert ****\vert *\)” corresponds to $x_3^4$;

- ”\(**\vert \vert ***\vert\)” corresponds to $x_1^2 x_3^3$.

This shows that we have exactly ${M+K} \choose K$ different monomials. If we restrict the monomials to have degree $K$, instead of $\leq K$, then we need to fix the last bar at the end. That gives ${M+K-1} \choose K$ options.

To avoid the cumbersome notation, in our development in this page, we will mostly be limited to the discussions on the bi-variate case with $M=2$, $K=3$, although our results can be generalized to more complex cases.

Our question is: given a set of input-output samples ${(x_1[n], x_2[n]; y[n]), n= 1, \ldots, N}$, can we learn the function $f$ efficiently? We will further assume that $(x_1[n], x_2[n])$ are samples from a bi-variate Normal distribution. Our goal is to use the knowledge of Hermite polynomials to construct a basis of this set of non-linear functions, and based on that, some good ways to learn the function from input-output sample sets.

For the purpose of defining orthogonal basis functions, we need a reference distribution, which we write as a joint pdf $r_{X_1X_2}$. For two functions $f_A,f_B$, we define the inner product as

\[\langle f_A, f_B \rangle \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \int_{x_1, x_2} r_{X_1, X_2} (x_1, x_2) \cdot f_A(x_1, x_2) \cdot f_B (x_1, x_2) \; dx_1 dx_2\]For the rest of this page, we pick the reference distribution as the bi-variate Normal density with zero mean, and covariance matrix

\[\Sigma = \left[\begin{array}{cc} 1 & \rho \\ \rho & 1 \end{array}\right].\]This might be confusable with our setting for Mehler’s Formula, which is explained here.

In Mehler’s formula, or equivalently modal decomposition, we try to decompose a likelihood ratio function $L_{XY}$ into the sum of simpler functions in the form of $\phi_k(x)\phi_k(y)$. This is similar to what we do here for multi-variate functions, where we also try to write $f(x_1, x_2)$ into sum of simpler functions.

The difference is that in modal decomposition, the orthogonality is defined for functions of a single variables. For example, the Hermite basis functions $\phi_i(x)$’s are orthonormal with respect to the standard Gaussian density. This basis allows us to decompose any function of $x$. We then extend the concept to decompose joint functions into modes. The likelihood ration $L_{XY}$ is a target function we decompose.

The study of multi-variate problems here, $[X_1, X_2]$ is considered one variable. The orthogonality is defined for bi-variate function $f(x_1, x_2)$, with the joint Gaussian density $r_{X_1,X_2}$ described above as the reference distribution. It is a coincidence that this is the same bi-variate density we try to decompose in the earlier problem.

- Theorem: Multi-Variate Orthogonal Polynomials Basis

- We take the reference distribution as a multi-variate Normal distribution ${\mathcal N} (x_1, x_2; \Sigma)$, the following set of functions ${\phi_{ij}}$ are a set of ortho-normal basis for real-valued functions over $x_1, x_2$.

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:multiHermite} \phi_{ij}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) = \phi_i (x_1; 0, 1) \cdot \phi_j (x_2; \rho x_1, 1-\rho^2)\quad x_1, x_2 \in {\mathbb R}, i, j = 0, 1, 2, \ldots \end{equation}

in the sense that

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:mv_basis} \int\int {\mathcal N}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) \cdot \phi_{ij}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) \cdot \phi_{kl}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) \; dx_1 dx_2 = \delta_{ik} \cdot \delta_{jl} \end{equation}

The Theorem is easy to prove, by writing

\[{\mathcal N}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) = {\mathcal N}(x_1; 0, 1) \cdot {\mathcal N} (x_2; \rho x_1, 1-\rho^2)\]and separately integral on $x_1$ and $x_2$.

The implication of the Theorem is, however, quite strong. We can write the basis function defined in \eqref{eqn:multiHermite} as the product of standard Hermite basis functions

\begin{equation} \phi_{ij}(x_1, x_2; \Sigma) = \phi_i(x_1) \cdot \phi_j\left(\frac{x_2-\rho x_1}{\sqrt{1-\rho^2}}\right) \end{equation}

That is, if we do not do the careful change of coordinate in \eqref{eqn:multiHermite}, but insist to use the standard Hermite basis functions, then the resulting multi-variate polynomials form an ortho-normal basis if and only if the variables $x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_M$ are independent, or, if we applied a whitening filter to pre-process them.

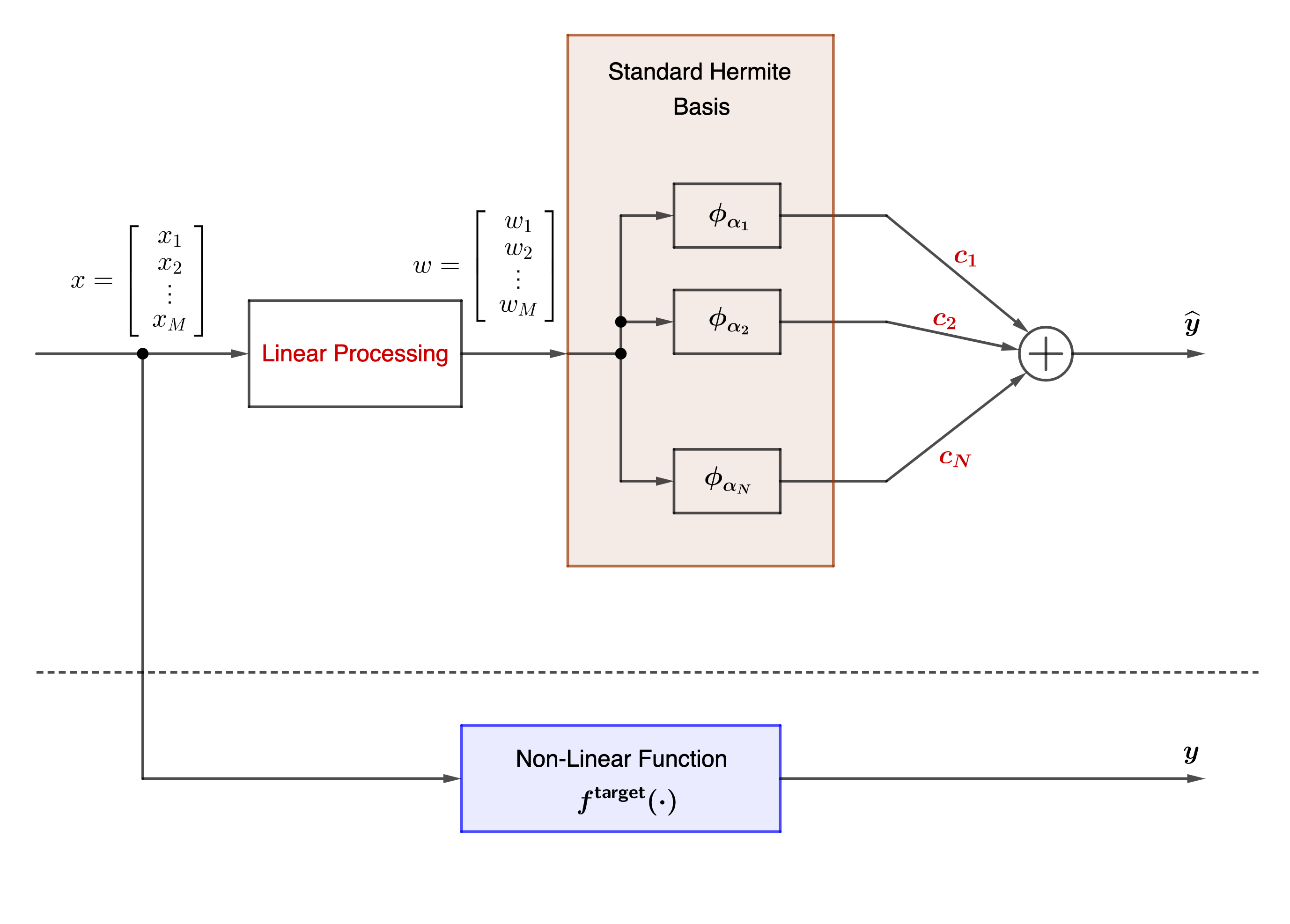

Separate Learning of Non-Linearity and Memory

There are a lot of applications of the above Theorem. We will discuss one that is directly related to machine learning. As we stated at the very beginning of this post, neural networks are powerful because it does two things. 1) it learns from the data the model of the statistical dependence between elements of the high-dimensional data, 2) it learns the right non-linear processing functions. Now, equipped with an orthonormal basis of multi-variate non-linear functions, we can analyze this process and the two learning processes. For that purpose, we consider an experiment illustrated in the following figure.

We set up this experiment as follows:

- The input is multi-variate data $\underline{x}=[x_1, \ldots, x_M]$ drawn from a multi-variate Normal distribution, with zero mean, and a covariance matrix $\Sigma$ that is assumed to be unknown.

- The target function is quite arbitrary, $y = \cos(\sum_i a_i \cdot x_i)$ for some unknown parameter $a_i$’s, or any other non-linear function.

- The linear processing is chosen in the form of an upper-triangular $M\times M$ matrix, with parameters to be trained (labelled in red).

- The output of the linear processing $\underline{w}=[w_1, \ldots, w_M]$ are fed to the standard multi-variate Hermite basis functions.

- The Hermit basis functions would form an ortho-normal basis if the input $\underline{w}$ has an i.i.d. standard Normal distribution. But, as we are training the linear processing unit, the input are in general not whitened.

- The Hermit basis functions we choose are obviously for $M$-dimensional input. We choose the polynomials up to a certain degree. In fact, we do not have to choose all such basis polynomials. In our experiment, we can randomly select a subset of these basis functions. We use $\alpha_1, \ldots, \alpha_N$ to denote the set of chosen basis functions.

- The goal is to form a linear combination

\begin{equation} \label{eqn:fhat} \hat{f}(\underline{x}) = \sum_{i=1}^N c_i \cdot \phi_{\alpha_i} (\underline{w}) \end{equation}

as a good approximation to the target function $f^{\mathsf{target}}(\underline{x})$. We would like to learn the coefficients $c_i$’s.

We assume we have a set of samples in the form of $[\underline{x}, y= f^{\mathsf{target}}(\underline{x})]$, and we want to minimize the L2 loss, $\vert y- \hat{y}\vert^2$. A neural network solution to this is straightforward: use $\underline{x}$ as the input and $y$ as the label to train a network, which mixes the linear and non-linear processing.

In our experiment, we separate the two goals. We use an iterative method. For a given linear processing, we learn the coefficients $c_i$’s by projecting the output $y$ to the output of $\phi_{\alpha_i}$, as if the $\phi_{\alpha_i}$ is one of a set of orthonormal basis functions. Then we simply form the sum in \eqref{eqn:fhat}, compute the L2 loss, and then optimize the linear processing coefficients.

So, what is going to happen? Take a guess!

Yes! Our experiment shows that the learned linear processing unit converges to the whitening filter of the multi-variate input $\underline{x}$! That is, the learning of the multi-variate dependence model and the non-linear operation is separated!

Here is the code for this experiment.